Through a loudspeaker hung near the decaying carcass of a poached elephant, we broadcast the bawls of a distressed buffalo. The calls ended in quiet. We scanned the bush with a red spotlight, less visible to cats than white light. Nothing. Ten minutes later we played the calls again, and a second sound became audible—a low, grunty-breathy huhn huhn, coming from the right. Keith Begg touched my shoulder. “Lion,” he mouthed.

Keith found the lion in his binoculars. “It’s Samora,” he whispered. “I can’t believe it. Exactly the lion we’ve been hoping to find.” Keith and his wife Colleen, who direct the Niassa Lion Project in northern Mozambique, had equipped Samora with a GPS tracking collar the previous year, but the lion hadn’t been seen for months. The Niassa team was eager to recover the collar and replace it with a satellite collar that would transmit the lion’s location several times a day.

Samora dug into the elephant carcass, and we heard crunching sounds. Keith peered through the sights of his air rifle and aimed at the lion’s shoulder. The dart hit, and Samora leapt. He sprinted twenty meters away, then collapsed into a deep sleep. Keith and his team worked efficiently to replace the old collar. They measured the lion’s height and length, drew blood, treated wounds, checked for parasites. The pattern of wear on his teeth suggested that Samora was about four years old—a mature male, ready to define a territory and mate.

I knelt beside him. He was fit, tightly muscled. I rested my hand on his flank, following the rise and fall of his breathing, then examined his feet. Samora’s forepaws dwarfed my hands. Too late, I remembered where those forepaws had just been, deep in the belly of a putrid elephant. Four hand washings later, the smell was eradicated from my fingers, but I still wished I’d brought some Purel.

Throughout Africa, lions are in trouble. Conflicts with local people, habitat destruction, inadvertent snaring and sport hunting are endangering this iconic species. Once numbering in the hundreds of thousands, fewer than 30,000 lions remain in all of Africa. In many regions, lions are killed in retribution for raiding livestock, or after injuring or killing local people. In Niassa, however, the major threat to lions is from snares set to catch other animals for meat. It’s illegal to kill wildlife in a conservation area, but the supply of domestic meat in Niassa fails to meet demand—a chicken costs three or four dollars, whereas a wild guinea fowl is only sixty cents.When heavy wire snares are set to target larger animals like antelope and buffalo, these snares inadvertently catch lions. Of the 22 lions that the Beggs collared between 2005 and 2010, ten died—five from snaring.

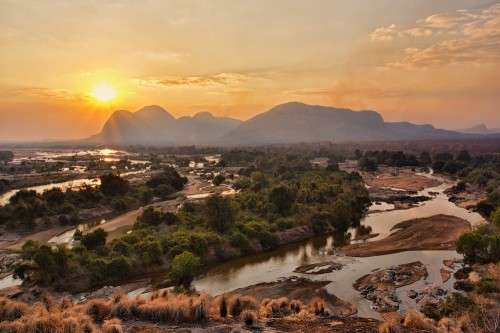

As Keith and I paddled a canoe down the Lugenda River, the chance of spotting a lion was minute—Niassa is vast, and its lions are shy. The chance of bumping into this particular lion was infinitesimally small. Yet there he was, lounging on a sand bar. Through binoculars we could see the satellite tracking collar we bolted around his neck three nights before, fifteen miles away. “Do you know who that is?” whispered Keith, incredulous. “Samora,” I answered. My skin prickled. We let the canoe drift. The lion strolled up the sand bar, then leapt up the riverbank. He dropped to his belly and draped a forepaw over the bank’s edge.

Watching Samora drowse in the setting sun, I felt awe. This unlikely meeting seemed fated, full of significance. I felt connected to this lion. I hoped one day to hear that Samora had established a territory and sired cubs, and I feared learning that he’d been shot, or snared. “Go well, Samora,” I wished silently as we pushed the canoe off the sand bar. He acknowledged our departure with a flick of his tail.

The day came sooner than I expected. “I think we’ve both been dreading having to send you bad news,” Keith wrote in an email. “Colleen received a mortality message from Samora’s satellite collar, followed by silence. We sent a vehicle round to the other side of the river, and I hiked into his last known position. As we approached, vultures flew up and we found his carcass and collar lying where he had been caught in a poacher’s snare. We found a second cable snare set for buffalo just 10 meters away.”

It was only two months after we saw Samora on the riverbank. I doubled over in front of my computer and sobbed.

Preventing snaring is a huge challenge. Increasing the number of anti-poaching patrols would help, but covering all of Niassa (roughly the size of Denmark) is hardly feasible—Mozambique is one of the poorest nations on earth. Instead of looking to the government, Colleen and Keith are working with local villages to introduce alternative sources of meat like domesticated guinea fowl, rabbits, ducks and pigeons, all considered excellent eating. And the Niassa Lion Project does more—they’ve sponsored Lion Fun Days to teach local kids about conservation, established a community center for environmental education and skills training, and raised funds for full scholarships to send children to secondary school (a first for Niassa). “People must choose to conserve lions,” argues Keith. “If conservation is in their interest and the benefits are there, other communities will adopt it as well.”

These programs have produced great results: in 2013, no lions in the Niassa Lion Project’s study area were killed in snares. Samora’s death in 2011 was one of the last. With luck, the Beggs’ determination, and funds to continue their work, new practices that benefit both lions and local people will spread throughout Niassa. Protecting Africa’s lions is possible—I urge you to take action to ensure that wild lions survive and thrive throughout the continent, now and into the future.

PROTECT LIONS THROUGH THE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION NETWORK

To learn more about how you can help save lions, visit Colleen and Keith Begg’s Niassa Lion Project on the Wildlife Conservation Network website at: http://wildnet.org/wildlife-programs/lion-niassa-0

Ivan Cordero

26 Oct 2014What an amazing collection. Thanks for sharing your work. It is trully inspiring. It is nice to know that some people still care about wildlife conservation. Ivan Cordero Wildatpalmas.com